How to bake the right support into instruction for multilingual learners

Do you like to cook? Can you call to mind one of your signature dishes? If you don’t cook, think of your favorite meal. What are the ingredients, and could it do without one or more of those elements? Maybe . . . but it wouldn’t taste the same, right? Have you ever inadvertently added too much salt—or not enough salt? Too much sugar? Not enough flour?

I’m getting somewhere with this, I promise!

Cooking is like the classroom; we need a delicate balance of key ingredients for multilingual learners to become proficient in speaking, writing, interacting, reading, and listening. But lately, the instructional pendulum has swung heavily toward phonics and reading, while writing, speaking, and interacting have moved to the back burner.

As a seasoned bilingual educator, I’ve seen trends in education ebb and flow—over the past 30 years or so—from whole language to balanced literacy to the science of reading.

From rhetoric to results

For the past 15 years, I’ve trained and coached teachers in schools throughout the country. One particular middle school I visited had 1,000 students, and roughly a quarter of them were English learners. Out of those 250 children, only seven reclassified as fluent English proficient the first year I consulted. The prior year they had two students reclassified as fluent English proficient (RFEP).

The teachers asked me, earnestly, “We don’t understand why more kids aren’t reclassifying.” But after doing one round of observations, it was crystal clear to me: These middle schoolers were sitting at computers all day, passively listening and reading. When were their active skills of speaking, interacting, and writing being utilized? Don’t get me wrong. I think online programs are crucial in terms of differentiating reading instruction and maintaining accurate assessments. It’s just that we can’t have that be the only ingredient in our recipe when teaching multilingual learners.

At that school’s next professional learning session, I asked a frank, rhetorical question: “If we want children to become fluent speakers, writers, and readers, what do we have to do?” The answer hung in the air like a weighted balloon.

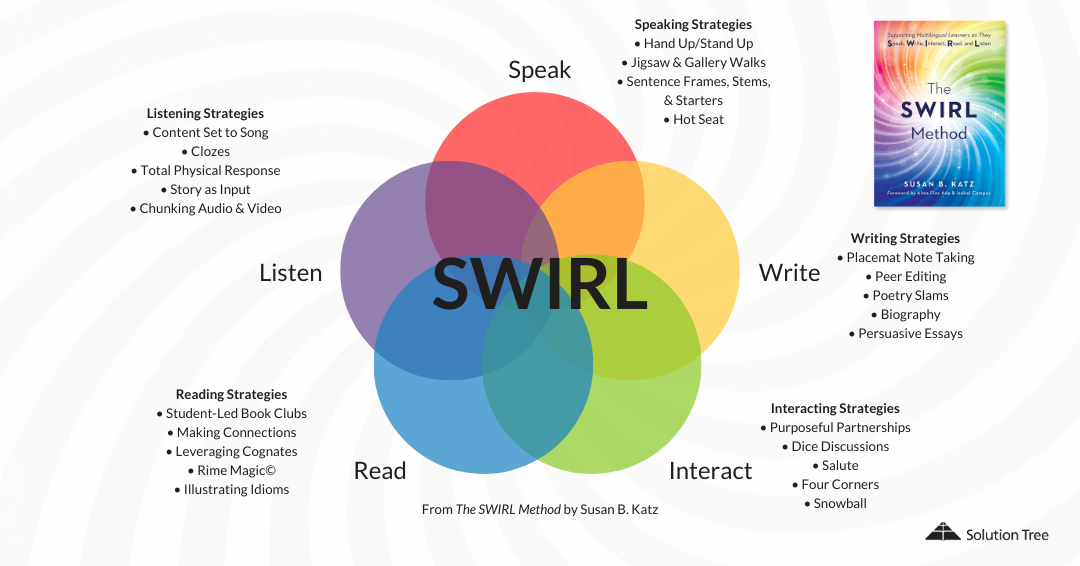

Then, I introduced teachers to the SWIRL Method: a framework and call-to-action to designing integrated, systematic English language development (ELD) instruction in each of the five core competencies (speaking, writing, interacting, reading, and listening). After a few weeks, teachers, students, administrators, and parents reported a palpable increase in opportunities, scaffolds, and supports that challenged children to produce rigorous, academic language. That is how we moved the needle. Now, let’s talk about how to blend our five core competencies/ingredients . . .

Five core competencies/ingredients

A cup of speaking

If we want children to be able to speak English fluently, we need to provide ample, structured opportunities for them to do so with fidelity and accountability. According to John Hattie’s research, the ratio of teacher talk time to student talk time is 89 percent to 11 percent. We need to flip the script and make it more like 75 percent student talk and 25 percent teacher talk. We can do this by using scaffolds such as sentence stems/starters and frames.

- Example of a sentence stem/starter: My favorite part was _____.

- Example of a sentence frame: The character did ____ [action/verb] which caused ____ [action verb] to happen.

Activities such as Jigsaw, Along the Lines, and Hand Up/Stand Up can help multilingual and English learners practice speaking and interacting. During a Jigsaw, students might read, discuss (speak, listen, interact), and write about a topic. Not only do we need excellent ingredients to ensure success in English, but we also need to mix them up.

A spoonful of writing

As an author of more than 80 books, I know that it takes a lot of practice, patience, perseverance, and persistence to become a solid writer. Learning to write can be a collaborative process as well. From peer editing to placemat notetaking, writing activities should integrate reading, listening, speaking, and interaction—however, the main flavor should always be writing.

SWIRL strategies such as Paint Chip Vocabulary Strips broaden students’ academic language by calling upon them to brainstorm lists of synonyms for words. They negotiate and rank the words to better expand these shades of meaning.

A scoop of interacting

People are naturally social creatures—and children are even more so. We want children, teens, and multilingual learners engaged in meaningful conversations via routines such as Socratic Seminars, Dice Discussions, and Four Corners.

Dice Discussions feels like a game and is easily adapted to various grade levels and content areas. You can use erasable markers to write response prompts on cubes from the dollar store (e.g., “describe the setting” or “who was your favorite character and why?”) or you can use regular dice and change the speaking prompts.

A serving of reading

There are few things that shifted my classroom instruction like teaching children to make text-to-text, text-to-self, text-to-world, and text-to-media connections, as described in Mosaic of Thought by Ellin Oliver Keene and Susan Zimmermann.

We also want to make sure that children are seeing themselves in the books they read. Given the efforts to ban books across the country, it is even more crucial that classroom and school libraries reflect the multilingual, multicultural students they serve.

“Books are sometimes windows, offering views of worlds that may be real or imagined, familiar or strange. These windows are also sliding glass doors, and readers have only to walk through in imagination to become part of whatever world has been created or recreated by the author. When lighting conditions are just right, however, a window can also be a mirror.”

—Dr. Rudine Sims Bishop

A dash of listening

Setting content to public domain songs increases retention of information. Take, for example, the song “Oceans Four” by The Levins (sung to the tune of “Row Your Boat”):

Row, row, row your boat, row from shore to shore

Pacific, Atlantic, Indian, Arctic, the major oceans four

Although the science of reading discourages three-cueing (picture walks and reliance on images to decode text), strategies such as having children cloze, by orally completing a sentence during read aloud, draws upon their background knowledge and understanding of rimes.

Making the case for SWIRL activities in the classroom

Educators need to implement these suggested activities outlined in The SWIRL Method now more than ever. Here’s why:

1. Our schools are welcoming an increasing number of newcomers. According to MigrationPolicy.org, “An estimated 649,000 children ages 5 to 17—representing 30 percent of all foreign-born children—had been in the United States for three years or less as of the Census Bureau’s 2021 American Community Survey.”

2. And HigherEdImmigrationPortal.org writes that “In 2022, first-generation immigrant students numbered 1.9 million or 11 percent of all students, representing a 41 percent increase from 2000, while second-generation immigrant students numbered over 3.9 million in 2022 or nearly 22 percent of all students, representing a 156 percent increase from 2000.” Teaching newcomers requires purposefully partnering students by same or different home languages and varying or similar English language proficiencies. It also means teachers would be wise to create a culturally-sustaining, welcoming classroom environment where home languages are valued as an asset not a deficit.

How we help kids speak up

3. We have a generation of children and teens who do not interact in the typical way that is required for language to be developed. Cell phones, video games, and online information shifted the necessity for real-life conversations. Add to that the pandemic, which literally had kids on mute for the better part of two years, and you have kids who are starving for opportunities to practice speaking, writing, interacting, reading, and listening.

4. The current focus on phonics and reading tipped the scales to the detriment of teaching writing and speaking. There are mountains of research proving that multilingual children succeed best when they learn to read and write in their home language first, springboarding off of cognates or crosslinguistic connections. Trending literacy instruction is subtractive (learning English at the expense of a child’s home language) versus additive (translanguaging and approaching the knowledge of other languages as a superpower).

Are you looking for more ways to support your English learners? These three blogs pair nicely with activities outlined in The Swirl Method:

About the educator

Susan B. Katz is a National Board Certified Teacher and award-winning, best-selling author. She trains teachers and principals all over the country on how to SWIRL with students, in support of multilingual learners becoming fluent speakers, writers, collaborative partners, readers, and listeners of English. Susan is the author of The SWIRL Method and will be a keynote speaker at Solution Tree’s upcoming Soluciones: Teaching Latino English Language Learners Institute in Bloomington-Normal, Illinois.