A thought occurred to me the other day while working with a group of singletons. “If I got to choose the questions that my singletons asked me, what would they be?”

Framing the Problem

What prompted my wonderings is that singletons almost always start with these questions:

- Who do I collaborate with?

- How do I create common assessments?

Most singletons get that common assessment is the linchpin of the PLC at Work™ process. They get that good common assessment practices are where the leverage is for better learning for students and adults. They usually feel that unless they can answer these questions meaningfully and completely, collaborating just doesn’t make a lot of sense. You know what? They’re right, it doesn’t. These are meaningful questions … but they’re not the questions I wish they were asking first.

Starting with a Different Question

Here’s the question I wish I heard first:

- “What do we really want our students to learn?” In other words, what learning is going to matter most to our students?

True, this is the first PLC question. So, why does it resonate so desperately and deeply with me as a starting place as I work with singletons? The first reason is that many teams, singleton or not, are overly focused on learning content knowledge. Skills are more enduring for success. Tony Wagner, co-author of Most Likely to Succeed: Preparing Our Kids for the Innovation Era, and expert in residence at the Harvard Innovation Lab, argues that knowledge is free and that transmission of knowledge only is obsolete. As Wagner points out, with information so readily available at our fingertips in an innovation economy, “it’s not what you know, but what you can do with what you know” that matters! (Wagner, 2015)

Content knowledge on its own shouldn’t be the goal. Instead, the 21st century skills are, in part:

- Can you ask questions?

- Can you sift through large amounts of informational text, determining what’s credible and what’s not?

- Can you use information from multiple sources in a creative way to synthesize a new claim and back up that claim using evidence from those texts?

- Do you have empathy for your audience so that you can communicate your ideas in a compelling way?

David Conley, professor and researcher at the University of Oregon, has written extensively about what it takes for students to be successful in the 21st century. He founded the Educational Policy Improvement Center, which explains, “Students need to do more than retain or apply information; they have to process and manipulate it, assemble and reassemble it, examine it, question it, look for patterns in it, organize it, and present it” (Conley, 2013).

I’m not saying content doesn’t matter, but the 21st century skills described above, among others, are ultimately the learning that will matter most to students’ future. Once teachers have made the shift in mindset from thinking collaboration has to be around common content to skills that transcend content, they are now ready to start talking about whom to collaborate with and how to create common assessments.

Once teachers have identified skills that really matter, the skills that transcend content, they are ready to find partners.

My book, How to Develop PLCs for Singletons and Small Schools, identifies several structures for singletons to be involved in the PLC process, two of which are vertical teams and interdisciplinary teams. Let’s use these to explore how teams could focus on essential skills, even if the content or grade levels are not the same.

- Vertical Teams: These are teachers who all teach the same subject but at different grade levels.

- Interdisciplinary Teams: As the name implies, these teams are made up of teachers who all teach different subjects.

A typical interdisciplinary team might be a high school social studies team. One teacher might teach US history, while another teaches world history, while another teaches government, while another teaches economics. The content of each is different, right? However, what skills do they have in common? Let’s say, for example, the team decided that they wanted to focus on the applicable 21st century skill of making and defending an argument. They could start by creating written models of what it actually looks like when a student performs that skill proficiently, what it looks like when students are approaching proficiency, and when student work is above proficiency. From there, they could create a rubric, describing why those models are quality work. Using the same rubric, they could set expectations based on grade level. “Here’s what your work needs to look like as a sophomore. Here’s what your work needs to look like as a senior.” The team could gather information (data) about the progress of each of their students. By focusing on the data, this team can improve their teaching. They can learn from each other the most promising strategies for teaching this very important skill. They can also use the data to respond to and improve student learning. In other words, they can follow the PLC processes, collaborating around skills that matter for student success.

What about elementary schools? A small elementary school with only one teacher per grade level could form vertical teams to focus on any number of literacy skills. Following the pattern described above, let’s say that a kindergarten, first-grade, and second-grade teacher formed a vertical team to focus on sentence writing. Although the expectation for proficiency is different at each grade level, the skill is the same. The team could share common rubrics, models of student work, and teaching strategies, and develop powerful intervention plans based on need, regardless of grade level.

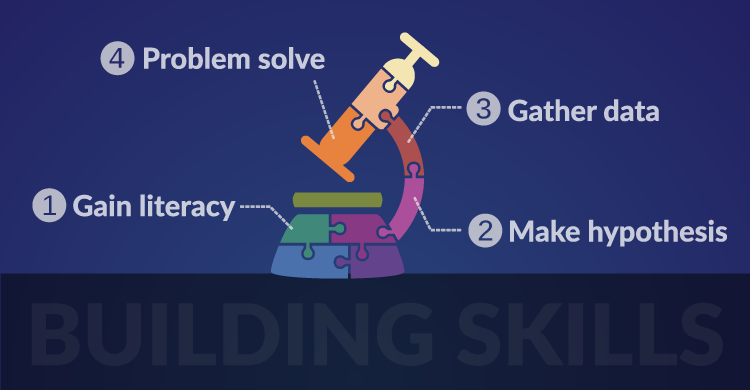

What about science or math? Science teams might choose a skill like using the scientific method to solve problems or make a hypothesis. Despite using different content as the vehicle for teaching such enduring skills, they can have rich collaboration. Math teams can focus on problem solving, developing common rubrics for approaching real-world problems regardless of the level of math being applied.

Music teachers can focus on essential components to effective performance or musicality, regardless of instrument or genre. A school-to-careers team might focus on the essential skills of being employable. They could clarify what employability skills really are and deliberately teach those with the same intentionality a traditional PLC team teaches their content.

The list goes on. The point is, finding a structure and a way to create common assessments becomes far less challenging when you start by asking the right questions. What do you want kids to learn—really? By focusing on skills that transcend content, you will be surprised by how much you really do have in common and how much it really does matter.

References:

Wagner, T. (2015, Dec. 23). Most Likely to Succeed. www.youtube.com/watch?v=AYwCkCecwNY.

Conley, D. (2013). Empowering Students for College and Career. www.epiconline.org.

[author_bio id=”13″]